Wairarapa house rentals have become the proverbial needle in a haystack. George Shiers pulls up the stats to prove it.

Those who want to rent a home in South Wairarapa are having to fork out almost $100 more every week than those in Carterton. Meanwhile, those who can’t even find a house must face an ever-growing waitlist.

The stark difference came as the government worked urgently to address what has been dubbed a “rental crisis”. There was a shortage of rental properties available in New Zealand and weekly rents were surging, yet policies from the government have failed to please either renters or investors.

There were just 32 rental properties available in Wairarapa on Trade Me as of yesterday. Of those, four were in Carterton, 13 in South Wairarapa and 15 in Masterton.

This was far below what was needed. In June, there were 198 people in Wairarapa on the Ministry of Social Development’s Housing Register.

The register contains applicants not currently in public housing who have been assessed as eligible and ready to be matched to a home.

In Masterton, 156 people were needing a home, there were 24 people in South Wairarapa in need of a home, and 18 people in Carterton, meaning all three districts had more people in urgent need of a property than they had properties available.

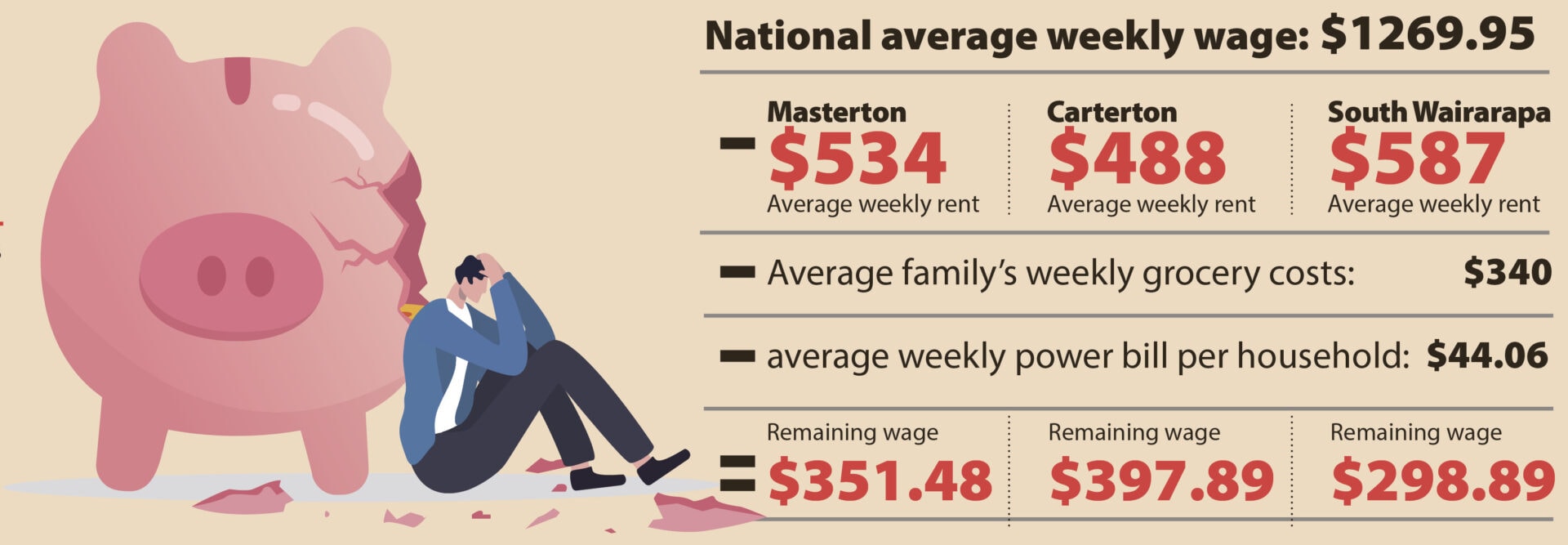

The average weekly rent for all of Wairarapa was $550. Broken down, Carterton was the most affordable of the three districts with an average weekly rent of $488, about $50 behind Masterton, at $534 a week. Meanwhile, South Wairarapa was by far the most expensive district in which to rent, with a home costing tenants an average of $587 a week.

Yet those rents were climbing fast. In April, the Times-Age reported that the average rent of houses available in Wairarapa was $508 a week and that the region had seen an annual average rent increase of $100, double the national average of $50.

Last week’s government announcement said that tax relief would be provided to landlords who bring new-built, long-lease rentals to market, but Wairarapa Property Investors Association president Tim Horsbrugh said the policy would only benefit high-income earners and would not increase affordable supply.

“Many tenants have been vocal in expressing how their rental prices have been increasing and that they don’t have a good supply of the kind of rental accommodation that meets their needs.

“While many claim that it is landlord greed causing these problems, these price increases are mostly a result of Government policies, such as removing interest deductibility.

“Tenant groups have said that there is a rental crisis, but allowing mortgage interest deductibility for high-end rentals will not solve anything for the majority of kiwi tenants. Interest deductibility should be reversed for all rental properties, not just high-end build-to-rent ones.”

A sentiment of disappointment in the announcement was shared by rental advocates. Renters United spokesperson Anna Bykova said rewarding long-term tenancies was the right direction to be going in but it was not enough to address the issue.

“At the moment, it’s common practice for tenancies to not be renewed simply because the owner is raising the price by an amount the current tenants cannot afford. Rules around long-term renting have the potential make peoples’ living situations less vulnerable to changes in the market.

“But the bottom line is that all tenants deserve the right to security of tenure, regardless of how many developments their landlord has.”

Bykova said it was uncertain that the changes would actually bring more houses to the market.

“For years we’ve been providing tax breaks to landlords hoping that they’ll get passed onto tenants, but we have yet to see that happen. So this policy will have some benefit for those who have the funds to choose but we don’t have much confidence that this will ‘trickle down’ to renters.”

Bykova said that whereas the change might be helpful in increasing supply, it was not going to bring as many new houses to the market as needed. She said that what was needed was an intervention to build properties that didn’t need to make a profit.

High rents were also the focus of an announcement by The Human Rights Commission [HRC] earlier this week. The commission called for an immediate rent freeze and an increase to the accommodation supplement as part of its housing inquiry.

The inquiry had found that rents were rising faster than income and inflation, with rents considered unaffordable for someone if they were higher than 30 per cent of the household income.

“The overall cost should be no more than 30 per cent of your income after tax being spent on your housing costs, but we know that almost half of renters do spend that or more and this is predominantly felt by those on the lowest incomes,” HRC housing inquiry manager Vee Blackwood said.

Blackwood said the current rental system was not designed for growth or the emergence of a “permanent rental class” – a group of people that would likely never own their own home.

Nationwide, the average salary was up 2 per cent from July 2021 to July 2022, according to statistics provided by Trade Me. Meanwhile, general inflation rose 7.3 per cent and rents rose 4.1 per cent. This meant New Zealanders were facing a real-term pay cut that would leave them with less cash in their pockets and less ability to leave the rental market.

Not all agree a rent freeze was the solution. President of the New Zealand Property Investors Federation Andrew King said chief human rights commissioner Paul Hunt failed to understand the reality of providing rentals.

“Why does he choose rental property providers to have their incomes frozen when rents have increased less than other living costs? Transport costs have increased 25 per cent so why not call for an immediate freeze on petrol?

“If Hunt wants to help tenants, why does he not call for a reversal in the three tax increases that are putting pressure on rental prices?”