The scene of a 2005 serious crash at the Norfolk Rd intersection. PHOTOS/FILE

How much will New Zealand invest in preventing the community transmission of covid-19 – is any dollar value too high? Newsroom’s Jonathan Milne investigates the price of life.

Andrew Graham was 18 years old. In his first year out of school, he had a good job at Kuripuni Motors, a steady girlfriend, and he was saving money to head to university.

“Life was going pretty good.”

Coming home from work, about 6.15pm on a Wednesday, he turned south on to State Highway 2 out of Masterton, heading towards the family farm on Norfolk Rd.

He remembers passing Solway Park Motor Lodge, and crossing the bridge over the Waingawa River.

Then he remembers waking up five days later in Wellington Hospital.

Witnesses pieced the rest together for police.

He had been waiting to turn right into Norfolk Rd; traffic was busy.

A drunk driver coming the other way at 140kmh overtook four cars that had slowed for the intersection – and wiped him out.

Graham suffered two small scratches from flying glass, bruises from his seatbelt, and a completely stoved-in skull.

The brain damage he suffered affects him still, at 47 years old.

He’s classified as an epileptic, he has to take medication every day so he can work and drive, he has suffered from depression.

The cause of the crash was a drunk, dangerous driver, no two ways about it.

But there was a contributing factor: an intersection that couldn’t sustain ever-increasing volumes of traffic.

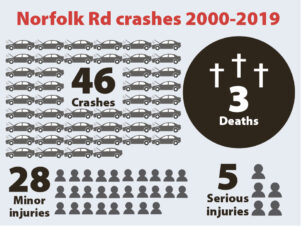

Records maintained by the Wairarapa Times-Age reveal there have been 46 crashes at the Norfolk Rd intersection since 2000.

There have been five serious injuries in that time, and three people have died.

Police note that the most recent death, a 66-year-old man injured in a crash in 2018, was actually found to be caused by a coincidental and spontaneous aneurysm rupture, two days later in hospital.

Despite his brain injury and the ongoing epilepsy and other health problems, Graham has built a career and, with his wife of 22 years, has three children who will soon be heading off to university.

One wants to be a civil engineer; he’s already done a research project on that dangerous Norfolk Rd intersection that nearly killed his dad.

These days, Graham is out working on a farm in Masterton, fencing the paddocks.

He wonders why it has taken so long to fix the road.

“The people making the decision do not have a personal interest in it.

“They can put all the economic values on it that they want, but this has been going on long enough now. It needs to be done.”

How officials value human life

How officials value human life

To be fair, it’s not as simple as Graham paints it.

Not quite. The Ministry of Transport and the New Zealand Transport Agency [NZTA] have a formula that they have honed over many years, for allocating scarce funds to roading infrastructure that is slowing traffic, choking economic growth, and endangering lives.

As part of that formula, the agency has a dollar value it places on what is delicately described as avoiding a statistical fatality. It is called VOSL, the Value of Statistical Life. It is, in short, the price of life.

In line with the latest cost of living increase, the Ministry of Transport updated that dollar figure in August. It is now $4.53 million.

Add in other costs such as emergency services and the vain work of hospital specialists, and the “average social cost per fatality” is $4,562,000.

For someone who suffers a serious injury, it is $477,600. A minor injury is valued at $25,500.

But these figures must also be weighed up against the social and environmental benefits of, say, reducing congestion on a busy commuter route.

Those are the numbers NZTA feeds into its computers, to help calculate whether it builds Transmission Gully, or a tunnel under Waitemata Harbour, or a roundabout on the corner of Norfolk Rd.

And more, these Ministry of Transport values placed on human lives are used by other agencies such as councils, health, and workplace safety, in deciding how to prioritise their spending.

Now, these formulae have new significance. It is the economic value that we place on a human life that is the unspoken calculation behind the biggest political question of this year and this election campaign.

How much will New Zealand invest in preventing the community transmission of covid-19?

Is any price too high to save us from coronavirus fatalities?

Counting the deaths

Norfolk Rd farmers Neil Wadham and Mark Graham [Andrew’s father] have spent the past 15 years battling for improvements to the dangerous intersection.

In that time, they have seen a new industrial estate built; traffic has increased dramatically.

Mark Graham speaks plainly: “It’s a shit of an intersection. It just about made an old man of me overnight.”

Wadham, who’s been on the AA local council and met with NZTA, says the intersection is no longer fit for purpose, with 22,000 vehicles up and down that stretch of highway every day, and big trucks turning across the traffic.

In July this year, NZTA announced it was designing a roundabout for the Norfolk Rd intersection, and safety barriers and a speed limit review along that high-risk section of SH2.

The intersection was finally deemed to be sufficiently congested, sufficiently dangerous to life and limb, to justify the spending.

At the same time, New Zealand was out of covid-19 lockdown, patting itself on the back for 100 days without community transmission, and merrily debating whether to open the borders to Cook Islands so Kiwis could take a tropical holiday.

Businesses wanted to be allowed to resume trading, locally and internationally. Their critics accused them of placing money before the lives of vulnerable people.

Somewhere in the middle has to be the answer: that always, we set priorities for scarce funds; that always, there is a sane and sensible balance to be struck between risk to human life and harm to the economy.

Why covid-19 is more fearsome than a death on the road

In 1991, government researchers completed a survey of 700 New Zealanders to find out what value they placed on safety.

They wanted to measure the amount society would pay for the avoidance of one premature statistical death – and they did it by asking individuals the amount they would pay for safety improvements.

They came up with a Value of Statistical Life [VOSL] of $2m.

A new survey in 1998 doubled the figure to $4m – but the government of the day refused to adopt it, seemingly dismayed at the cost implications for road, rail, and aviation infrastructure.

So it is that the flawed 1991 survey result has been updated in line with inflation, every subsequent year. Extraordinarily, that outdated and discredited survey is still used to decide whether or not to build transport and other infrastructure

Almost since the beginning, there have been voices questioning whether VOSL provides a good measure of how much the community should pay to minimise the risk of death and injury. One such voice is Dr John Wren, who was principal research adviser at the Accident Compensation Corporation [ACC].

Wren lives in a cottage near Carterton Rugby Club, just five kilometres down SH2 from the Norfolk Rd intersection.

It was he who suggested that particular crash blackspot as an example of the difficulty applying the VOSL calculations in real life.

“How many deaths and serious injuries before NZTA will do something?” he asks.

Covid-19 exposes the limitations of this economic model and indeed, the Ministry of Transport now says it intends to replace the 1991 methodology.

One question is whether New Zealanders would like government and other big organisations to pay more to protect them from certain types of death that they especially fear. This is known as the “dread” factor.

In the UK for instance, health authorities will pay twice as much to minimise the risk of death from cancer. And the Government will pay 10 times more for safety measures around nuclear power plants, because surveys show residents dread death in a nuclear accident 10 times more than they fear death on the road.

So, is there a similar dread factor around covid?

There’s not yet been any research, but anecdotally, it seems the public and politicians express a greater aversion to the risk of death from the coronavirus.

Dr Paul Frijters, a visiting professor at the London School of Economics said: “To prevent a death marked as due to corona they have been willing to spend well over £1m per year saved. To prevent a death not marked as due to corona, they have basically not been willing to spend much at all”.

“To save a person from corona, the New Zealand government has been prepared to damage its own economy such that many more over time will die, and the quality of life for the whole population will diminish much more than if they’d simply ridden out the virus.”

Let’s be clear, Frijter’s view is not mainstream. New Zealand economists told Newsroom that they agreed covid-19 was treated disproportionately – but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. This is a disproportionate disease; it breaks many of the old models.

“I do think there has been an element of a ‘dread’ factor with covid-19,” John Wren says.

“The dread was looking at Italy and saying let’s learn and if we don’t act now there is no reason to say it won’t happen here.”

This is slightly different from the traditional dread model; which found people were especially repulsed by dying in manners that were perceived to be more unpleasant.

What Wren describes here is a more systemic dread that goes beyond individual fears; that rightly recognises the potential of this killer virus to spread in a way that a dangerous road intersection cannot.

- This article was republished with permission from Newsroom.